When I was a boy, there was a mysterious elderly lady who lived in an old decrepit house on the corner of West 6th and North High. Sadly, she was the subject of a lot of jokes and wild stories, mainly because she sat on her porch in all kinds of weather, surrounded by chickens, and occasionally with a side by side shotgun across her lap.

Nobody, especially a kid of twelve years old, considered that she had an especially rich past tied to the very founding of Maury County.

Elizabeth Pillow “Lizzie” Porter’s grandfather William Porter (1773-1843) was from Tamna Wood, near Ballindrait, County Donegal in the Ulster Province of Ireland. He had migrated to Tennessee by at least 1816.

When he passed away, his son William Taylor Porter (Lizzie’s father) was only 15. William Taylor had two sisters, one of whom (Mary) would marry South Carolina merchant and Revolutionary War soldier, Samuel Fulton Mayes, and build Mayes Manor in 1858, very near the Porter home.

William Taylor Porter was Quartermaster Sergeant for Company C of the 9th Battalion, Tennessee Cavalry. He died during the war, one month shy of his 36th birthday, when Lizzie was only three years old.

Her mother, Mary Pillow Porter, was just 26 years old when her husband — as well as, her father, William Hartison Pillow — died. Besides, Lizzie, she had a six-year-old daughter Lula and an infant son, William Taylor, Jr., who was less than one month old.

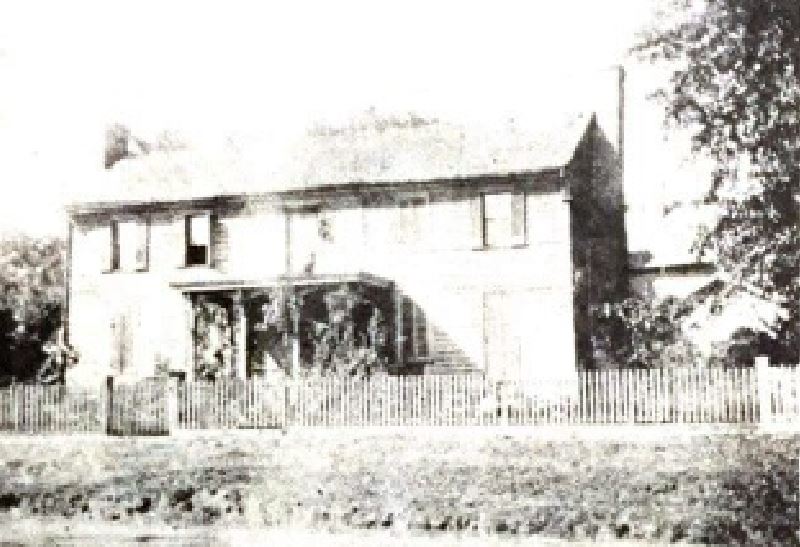

They lived in the house on West 6th, which was constructed with cedar logs in 1816 for Samuel Craig by a local carpenter, James Purcell. A worker on the project “bound” to Purcell was master builder Nathan Vaught, who went on to build grand homes such as Walnut Grove, the Anthenaeum, Elm Springs, and Hamilton Place, among many others.

Mary lived until she was 90 years old and never remarried.

Incidentally, Mary’s grandfather was Abner Pillow, a Major in the War of 1812. After the war, he surveyed, owned and developed land across Middle and West Tennessee. His brother William and he purchased the first lots sold in Columbia, beginning April 1, 1808. He also owned a large plantation near Old Mt. Hope Church.

One of his claims to fame was the killing the Indian Chief Big Foot in a hand to hand fight in the middle of Duck River:

“Abner Pillow had a fierce and terrible combat with a fierce and athletic Indian in the water of Duck River. Both parties had emptied their rifles and then grappled in deadly conflict in the water about four feet deep, Abner armed with a sharp butcher knife, and the Indian with a tomahawk. In the midst of the struggle both parties went under the

water. While in deadly grapple under the water, a plunge of Abner’s butcher knife into the heart of the Indian decided the battle.”

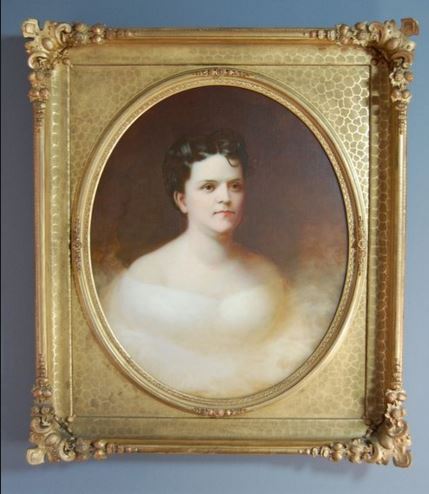

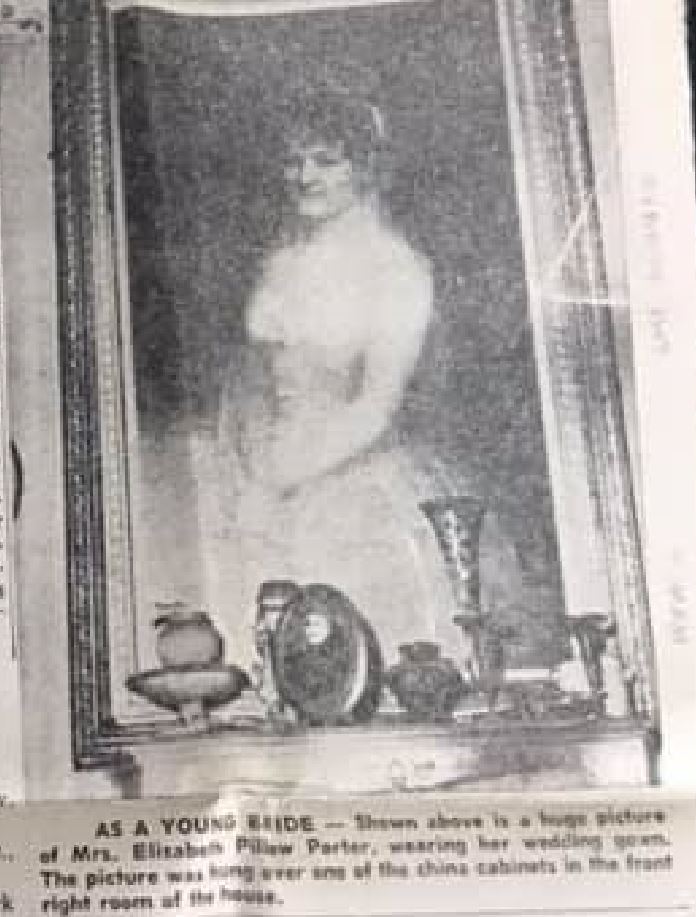

Having come from a prominent Tennessee family, Lizzie Porter joined into marriage in 1883 with Nashvillian William Woodfolk, the son of a once-wealthy landholder from Jackson County, Tennessee. She was 22 and he was 48.

Unfortunately, toward the end of the decade, Woodfolk was embroiled in a series of inheritance and debt litigations, contributing to the marriage’s dissolution by 1890.

In 1897, at age 36, she married a second time, to the widower William Henry Watson who was 52 and owned a livery stable. He was likely a friend of her father’s for he also had served in the 9th Cavalry – in Company G.

William and Lizzie lived together in the house on West 6th until at least 1900 but, by 1910, William was living with his daughter. He died in 1913.

Some time after her mother died in 1928, Lizzie took in boarders. One of them was my grandfather’s brother Willis White, a local policeman. Because of Willis, I was handed down a dinner bell and bird bath that once graced Miss Lizzie’s backyard.

Willis died in 1939, and my father believed the old car they found in Miss Lizzie’s garage was his.

Speaking of my father, Jack White, he worked for the Railway Express Agency, and every year he would deliver oranges in the winter time to Miss Lizzie’s front door. They were sent from a nephew who lived in Los Angeles.

Miss Lizzie was hard of hearing so she left a rock on the front porch that delivery men were to hammer against the door frame where she could hear them. A portion of the frame had been beaten to a smooth bowl shape over the years by this practice.

One cold winter morning, my father was standing on the porch by an old couch covered by an even older wool rug, and he was holding a crate of oranges in one hand, as he used the other to pound on the door with the rock.

Suddenly, a deep, ghostly voice emanated from beneath the rug.

“Yeeeees…”

It was Miss Lizzie.

Miss Lizzie died October 24, 1965 at the age of 104. The following year the house was torn down and her valuable — and not-so-valuable — possessions were auctioned for charity.

Lizzie and all her Maury County Pillow and Porter ancestors are buried at Rose Hill Cemetery.